Meg Mullins

Dirt

Meg Mullins

Dirt

T

he house had been in his mother’s family for years. Early in their marriage, his parents had spent the time before his birth restoring it together. There are photographs in a box underneath his mother’s bed that show the both of them with bandanas tying the hair off their faces, tools scattered across the downstairs porch, a small set of windows along the kitchen wall where there is now one, long stretch of glass. The house was like a first-born child, perfected through the careful attention of its parents.

In the divorce, they fought over the value of the house. In adult maneuvers George didn’t quite understand at the time, it mattered to the court what somebody else, a stranger, might pay for the house and so there were a series of men in plaid shirts who came over to look at the carved woodwork, plank floors, and plastered walls. Inevitably, they’d stand on the porch and look at the distant line where the sky rested on the land. Gem of a house, they had all agreed.

In the end, George’s mom was given the house. And George. So they lived there together, on a vast and beautiful stretch of land outside of town.

#

These days George doesn’t spend much time inside the house. When he arrives home from school his mother is playing her music through the stereo and standing in front of the easel she’d assembled in the room that used to be his parents’ bedroom. It has a view of the eastern horizon and long, anguished shadows stretch across the room for most of the morning. Her paintings are of these shadows, assorted dark shapes marking the impact of an object when struck by the rising sun.

Meanwhile, George roams the three acres alone. There used to be neighborhood kids who were allowed to come play, but not anymore. Often, George walks with a stick in his hand that he uses to beat a rhythm against the dirt and the rocks he passes. School has just let out for the summer. On that last day, he’d come home and curled his head into his pillow, crying with relief.

His mother has called the kids at school cruel, but to George just about everything they said was right. There was truth in their teasing, their ridicule. Who could blame them for saying the things they noticed about him? When they wondered aloud why he was alive, he shook his head, equally confused. When they told him he was tainted, evil, even, he couldn’t be sure they weren’t right. Some days the teasing felt good, like a punishment he deserved. But other days, he wished they would just beat him to a bloody pulp and put him out of his misery.

Even Miss Conley seemed unsure of what to say to him. She had never met his father, but what did it matter now?

At night, his mother would sit on the edge of his bed and run her fingers across his back. She told him stories of wild horses, thunderstorms, and rattlesnakes. She told him that all lives involved pain. Theirs was not unique.

He knew that by consoling him, she was also talking to her own pain. No doubt his mother was sad. Together, they had driven in her station wagon with a bouquet of grocery store flowers and laid them on the doormat outside the girl’s apartment door. In the mailbox, his mother placed an envelope of cash. Back in the car, she bent over the steering wheel as she wept. George slid down in his seat, afraid.

One night, he took a deep breath and said, But what about the pain we’ve caused, Mama?

Her eyes darted away from his. George, she said, into the darkness. Just his name. It was his father’s name, too. Her voice quivered as she spoke. You haven’t caused any pain. You are innocent in all of this.

And then she pulled him up from his bed and held him in her arms as she cried. She rocked him back and forth as though she were the ocean and he was a boat.

But George knew the truth. He knew that he was not innocent. And the more she cried for him, worried about him, the worse he felt.

Only when he walked through the brush, the sun gradually becoming hotter on the top of his head, beads of sweat rolling from his armpits down the sides of his ribcage, did he find a place outside of the past. Sometimes he sat in the thin shade of a juniper bush and watched the lizards move through dirt, the noise of their feet like a perfect incantation. He watched one carefully, waiting to see if it would be plucked by a hawk or a snake. When it wasn’t, he found himself wondering why. He looked to the bleached, empty sky. What could account for this lizard’s good luck or his own bad luck? How, he wondered, were our lives unfolding the way they were?

#

When his father had arrived at the house that day, his mother was already painting. He remembers that she seemed moody, as though she knew he was coming, but she hadn’t mentioned it to him. Still, there was music, and she fixed George a hot cocoa and he was half-heartedly playing with an old purple Matchbox car, rolling it over all of the boxes of paints and jumping it from chairback to table.

George remembered that, as the front door opened, it swung against the wall and the surprise made his little car fly out of his hands.

It had been nearly two months since his father had come for a visit. Since Christmas, he guessed. With his mother, the days were full of grilled cheese sandwiches and apple slices, candlelight on the porch for dinner, milk in a crystal goblet, listening endlessly to the Beatles’ Abbey Road on vinyl, painting faces and moons and stars onto the rocks he’d collected, throwing the heavy horseshoes at the metal stake in the ground. Why, then, was it his father he longed for?

Poppy! George had run down the stairs and into his father’s arms.

He showed up in faded blue jeans and designer sunglasses. His face was darkened by whiskers that scratched against George’s cheeks and made him feel the closeness of danger. After an embrace, his father told him to get his shoes on.

When he came back downstairs, his mother and father were standing opposite each other just outside the door on the wide, brick porch.

He’s not a trophy or a plaything, George, his mother said, her arms crossed.

You think I don’t know that? He’s my son.

Here, George’s father saw him and reached his hand out to him. He’s my pal, he said to them both. As George walked past his mother toward him, he heard her sigh.

Have him home for dinner? Tomorrow is a school day. Please, George?

Both he and his father turned toward the sound of their name. George nodded, thinking of how he would tell his classmates that he rode in the cab of his father’s truck, ate fried chicken out of a bucket, and caught a ten-pound fish. These were the promises that had been made last time.

As George buckled into the seatbelt, he looked through the windshield at his mother standing in the doorway. He knew she would wait to close the door until she saw the truck turn out the driveway onto the main road. This diligence, this observation made him feel small, vulnerable.

And as his father turned the truck onto the highway, George rolled down his window and felt the freedom of freedom. He and his father were escapees. His father had pulled a cigarette from his pocket and handed it to George so that he would light it for him. They were running away from everything together.

But after burgers at the diner and his father’s third beer, George began to think about the way the sunlight would look in his mother’s studio. He imagined her bare feet and the hot cup of tea she would hold between her hands as she swayed in front of the window.

His mother keeps jars of dirt in her office. From all the places she’s been on planet earth. There must be a hundred of them. All different colors and textures. There was dark red clay from Arkansas; pale, gray dirt from Israel; a sandy, rocky mixture from Arizona; a fine white sand from St. Croix; sea pebbles from Marseilles.

We haven’t even begun to dust up this town, son, his father had said as though George had said something aloud.

He nodded and ordered a chocolate sundae and handed his father the cherry on top.

There was more beer but that was nothing new. Sometimes his father drank too much when he was happy and sometimes when he was sad. Often, George couldn’t tell which was which.

When dusk approached, they had spent nearly an hour and a half in the bar near the elementary school, shooting pool and throwing darts. There were three or four other men that gave his father a game of pool. George and his father were a team, his father allowing him to hold onto the cue, choose the angle. Then, his father would take a sip of the whiskey he’d started drinking at the bar and wrap his body around George’s, adjusting their aim ever so slightly. The force of his father’s shot passed through George and into the ball.

#

The thought of it now—the power of his father’s shot—makes his ears rattle and his vision fuzzy. He stands up and keeps walking. Sometimes his body felt like a trap, his arms and legs holding him hostage, keeping him slow and tethered. But how to escape?

Out in the heat, his scalp burning and his fingers throbbing, it is easier to block out the rest. The endless blue sky and the nearly white blaze of the summer sun create a blankness within him. His mind empties as he moves across the landscape, stopping only to follow the arc of a bird’s flight or to study some ants dragging a dismembered insect wing into their hill.

He returns to the house as the cool of sunset approaches, his skin tawny and dusty. There is music on, a pot of beans simmering on the stove. He leans his head in front of the kitchen faucet and lets the water run over his cheeks and into his mouth.

George, his mother says, hearing his footsteps on the stairs. Come tell me something.

She stands in front of the canvas gripping her brush. He moves in beside her, droplets from his face already evaporating. She places her hand on top of his head and he can feel the sand scratch against his scalp as she moves her fingers.

Do you think the blue is too saturated?

He scans the painting. It is one of her smaller ones, just the size of a piece of notebook paper. The shadows are indistinct, but one has a loop like the pull on the roller blind that hangs from the top of the window.

George doesn’t see any blue in the painting. He sees gray, black, a shiny bit of yellow.

Her palette is still covered with wet paint and George notices a small pile of deep blue paint, but when he looks at the canvas he cannot find it anywhere.

I think it’s just right, Ma, George says.

His mother glances at him, then back at her work. Go have a bath. I’ll clean up here and then we’ll eat.

As George sits in the bath, he thinks about his father. He wonders if the prison has bathtubs. Since prison is the worst kind of punishment, he assumes it must not. And then, suddenly, he forces himself to stand up from the warm water and turn on the shower head. He hates the way the water pelts his head and back, but he endures. The shower curtain curls in and sticks to his bare thigh. He pulls it off and shivers with disgust. Eyes closed, he reaches for the faucet and turns it off.

Listening to the last of the dirty water drain out of the tub he realizes that surely the prison must have drains. Even if there are only sinks for the men to brush their teeth in, there have to be drains that leave the prison and take the dirty water away. So, he crouches down with his ear over the bathtub drain and listens. He hears a far away whistle, then a gurgling and a wide, empty calling. Like the noise from the inside of a seashell. He lets the noise enter him. Then he turns his mouth to the drain and whispers, Poppy, Poppy, Poppy.

At dinner, his mother asks him to tell her about something that he saw today that he loved. Sometimes she was weird like this.

Dunno, he says, sipping the broth from his bowl.

It’s okay if you want to keep it for yourself. She shrugs and takes a cucumber from the bottom of the salad bowl. I looked in on you this morning and saw your left foot sticking out of your quilt. There was a smudge of dirt along your heel that looked like a shooting star.

George smiles. This image pleases him, but he doesn’t bother looking at his bare foot now. He knows that his mother often sees things that he can’t.

That night, as he lay in his bed, a light from a car’s high beams on the road skims across his wall. He shuts his eyes tight, but it is too late.

#

They had left the bar and his father placed his hand on George’s head, steadying himself as they walked down the alley to the truck.

Did you see me hit that bull’s-eye, George? Three times. You’re my lucky charm.

George had grinned. From where they were parked, he could see the playground of his school. The abandoned swings, the seesaws and basketball court. He felt hopeful knowing that everyday at recess he would be able to look at this spot and remind himself of those words.

His father sat behind the wheel and handed George another cigarette to light. What now, son?

I wish you could see my classroom, George heard himself saying. He did want his father to see his name on the bulletin board of Good Citizens, he wanted to reveal to him the stack of perfect multiplication tests in his desk, and point out the cozy corner where Miss Conley let him read nature magazines and write down interesting facts. But right away he knew it was reckless, and he wished he hadn’t said it.

His father nodded and took a long drag on his cigarette. Let’s go see if we can get in, he said, and George blushed.

No, Poppy. It’s too late. You could come tomorrow. Maybe even pick me up after school? I could show you all around.

But his father had already put the truck in gear and was turning the corner. For a moment, George thought that maybe they would be able to get in. Maybe Miss Conley would be there, sitting behind her desk grading their papers, making the origami creatures she surprised them with on Mondays. He imagined her face lighting up when she saw them, so happy to finally meet George’s father.

As soon as he saw the building, its windows all dark, he knew this was a mistake. But his father had committed. He turned quickly, sharply into the parking lot and his headlights flashed across the building, lighting up its brick facade and then, suddenly, the girl on the bike.

George saw her ponytail, not her face. His father saw her, too, but because of all the drinks, they said later, he mistook the gas for the brake. The truck accelerated into the bike and dragged it before his father figured out which was which and hit the brakes hard. He had jumped out of the truck with his lit cigarette while George stayed buckled. He was embarrassed, afraid it was a girl from school.

But it was not a girl from school. She was fourteen and had just moved into the neighborhood. Her own father had bought her the bike that afternoon from a garage sale.

Soon enough, George heard his father on the phone, screaming at someone to get him some fucking help. George turned and looked out the back window and saw the metal of the bike twisted, the girl on the ground.

He unbuckled and stood just behind the truck, watching his father’s hands tremble as he tried to cradle the girl’s head. George thought it was the whine of the truck’s engine, but then he realized the girl was moaning. His father was crying, which George had never seen before. Slowly, he walked toward his father and picked up the cigarette from where he had dropped it. He held it the whole time. It burned down to the filter and still he held onto it. Past when the ambulance arrived and when they lifted her onto a stretcher, past when the police handcuffed his father and sat him in the back of the squad car, past when his mother’s station wagon turned into the parking lot and she ran to George in her nightgown.

The girl lived for three days in the hospital. George’s father was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. George took his own name off of the Good Citizen bulletin board and threw it in the trash, but he didn’t know what else he was supposed to do.

#

George gets out of bed and opens the bottom drawer of his dresser. He digs into the back pocket of the pants he’d been wearing that night and removes the brown filter. Carefully, he holds it between his lips. He feels close to his father and also adrift. George had lit this cigarette when he was lucky and the girl was alive and his father was going to take him home.

He wonders why his mother still loves him. He wonders why his heart still beats.

George takes the cigarette stub from his lips and cradles it in his hand.

There is so much wrong with everything, he thinks. He can’t get back into bed. He stands in his doorway, listening to the sounds of the house.

Ma? He calls out into the darkness. Ma?

But she doesn’t hear him. George creeps to the stairs and sits on the top step. He looks down at the front door, remembering the feeling of possibility it used to hold for him. It used to be that there was a chance, at any moment, his father would arrive and bring with him something of the larger world. Now, it was ruined. It was just a door.

And then he imagines the girl’s front door, also ruined.

George can never make that better. He will always be this boy, whose father killed a girl.

His mother says they’re not alone in their pain, but George doesn’t believe her. Lots of people have pain from how unfair life is. But that’s not his pain. What he has lost, he deserved to lose.

He stands up and lingers in the doorway of his mother’s studio.

The shadows that she paints over and over again are pictures of things she’s lost.

And the jars of dirt are also reminders of places she’s lost.

It occurs to him that she should throw out all of the sand. Why would she want the landscape of another place here? Why would she want to remember everything she’s lost? Why does he? If only he could forget, he might be free.

Running his fingers across the tops of the jars, he stops when he reaches the one marked home. It’s too dark for George to see, but he knows the texture of this dirt well. He turns to the quiet of the house, waiting to see if his mother will stir. When she doesn’t, he carefully unscrews the lid, takes the cigarette butt between his fingers and shoves it deep into the dirt.

For a moment, he feels lighter. He replaces the lid and walks back to his bedroom, empty-handed.

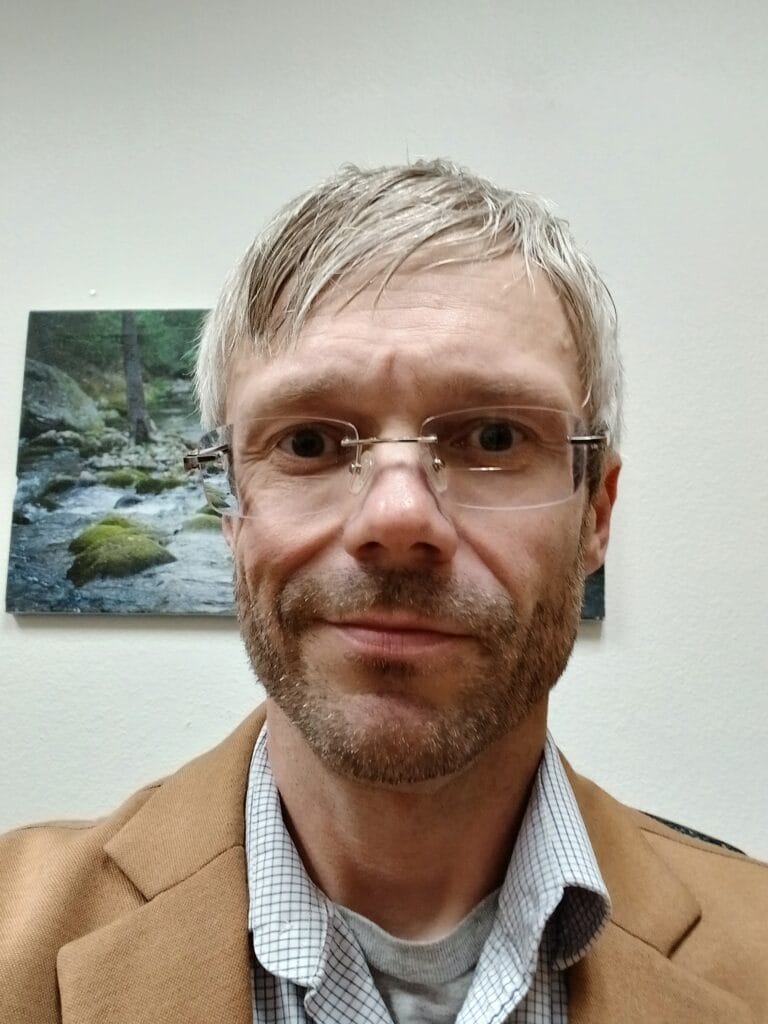

Meg Mullins is the author of three books published by Viking Penguin: The Rug Merchant, Dear Strangers, and This is How I’d Love You. Her work has been translated into eleven languages and optioned for film. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous journals and has been included in The Best American Short Stories. Her first collection of stories We Are All Having Fun Here will be published in 2026. She was born and raised in New Mexico and happily returned there to raise her own children.

Featured in:

Red Rock Review

Issue 55